The addiction to weapons is killing us. If everything looks like a nail, then the hammer looks like the correct tool. But what if that’s a misdiagnosis? The response to threats of violence in our culture is predisposed to applying weapons to address any threat. We even use weapon-related language when addressing disease, climate change or inequality, i.e., “target”, “war on”, “attack”. But nowhere is this so dramatically visible than with both our militaristic mindset and our addiction to guns for personal security.

We’ve been chasing this tail without success for way too long. There is plenty of data to suggest that this addiction is making things worse, both in international relations and in our neighborhoods. To challenge the addiction publicly is to be labeled “soft on communism”, “a patsy”, “unpatriotic”, a “freedom-hating liberal” or a “Second Amendment denier.”

We have manufactured and distributed so many weapons that now other nations and individuals look to their arsenals when they find themselves in a conflict. Sometimes they only brandish their weapons to demonstrate how tough, manly, or strong they are. But with so many weapons now in so many hands, we see increasing eruptions of deadly violence everywhere, across borders and within them, and in our schools, shopping malls and leisure places. How is it that to even suggest constraints on weapons is anathema to our sick culture? Congress has shown only tepid solutions, like child locks on guns, which they can’t even agree on. Spending on weapons of war has no limit in the eyes of the vast majority of members of Congress, only on how much to increase this theft of the common wealth. This is what in systems thinking is known as a negative reinforcing loop: More weapons in more hands equals more deadly violence, requiring more weapons.

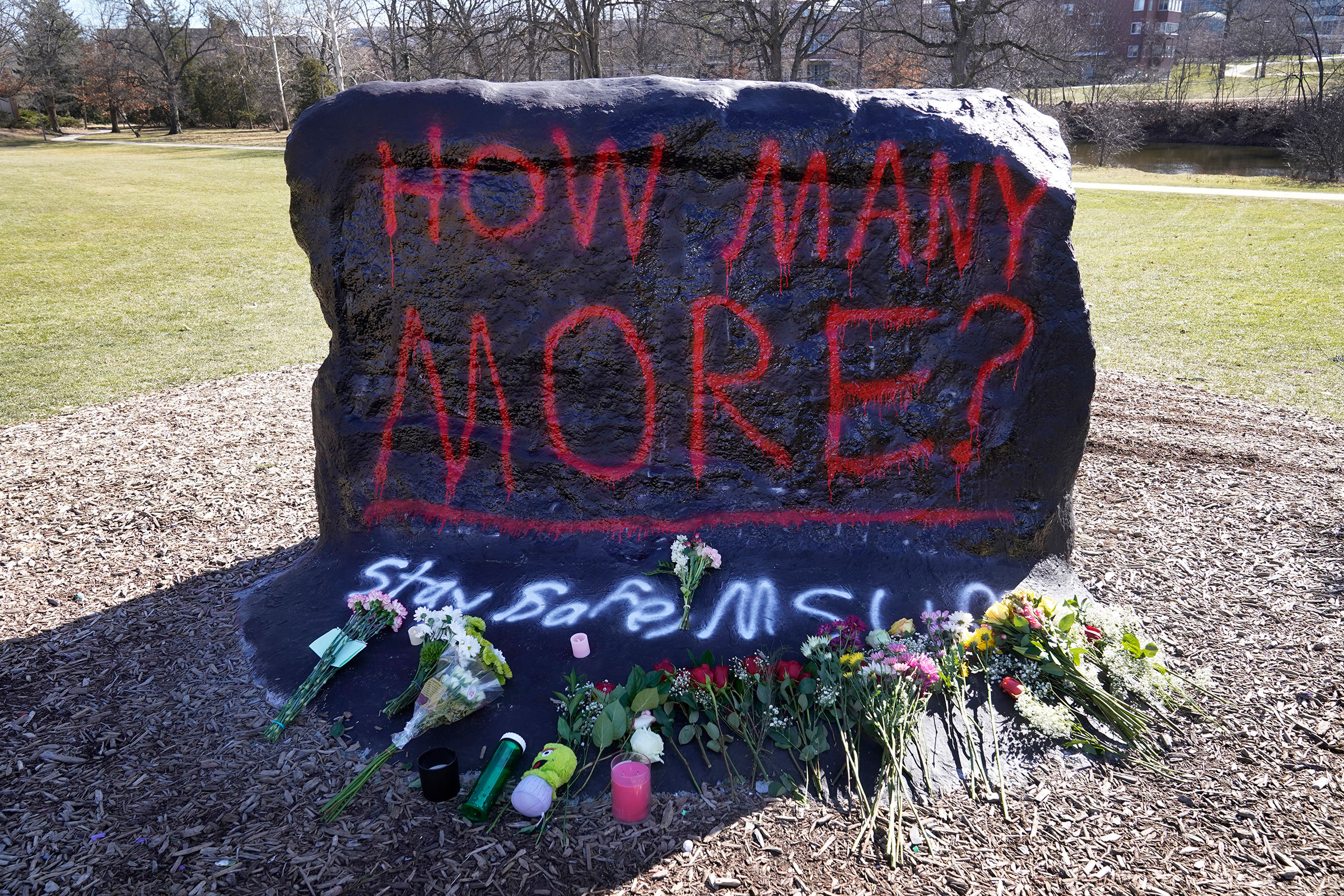

Having students murdered this week in the building I used to teach in certainly has sparked my attempt to look at the larger system of weapons mania and the unintended consequences of our failed solutions to violence at home and abroad. It brought back vividly my own experience with gun violence 50 years ago as a student at Wayne State in Detroit.

It was a chilly November morning and I had been drinking coffee in the student union before heading across the mall in advance of my next class. There were few people on the mall between class times when I heard gunshots near the library. I saw a victim fall and the shooter run away. Without thinking, at least I don’t recall giving it any thought, I ran to the victim, a young African American student lying on his back, blood gurgling from his mouth and his eyes wide open in shock. I can see them now as clearly as I did that day. I quickly took off my coat and put over him and held his head up trying to keep him from choking until police arrived and medics came and moved me away. I walked around for a couple of weeks trying to find some balance in the world. I had been involved in numerous anti-war demonstrations and was leading a Free University course on the idea of "nonviolence". Experiencing gun violence first hand just put me in shock, as I assume all who witness murder must. I learned later that the young man died, the shooter was caught and I assume, eventually convicted.

As I was then, I’ve been wading in the mud (or is it quicksand?) of the spiraling decline of our common wealth via increasing military spending for the better part of the last decade. What is crystal clear from my studies over that time, as clear as the eyes of that gun victim are to me today, that despite this growing arsenal of weapons, we feel no safer either on the global stage or on our city streets.

It was while reading a book on systems thinking the morning after the recent MSU shooting that I reflected on how our elected leaders, and too much of the public, are simply addicted to guns and weapons as the answer to insecurity. It’s not surprising, given how our culture is obsessed with violence (been to a movie theatre recently?). No doubt there is great financial profit in the violence industries. Selling security via weapons is indeed lucrative--even during the pandemic those merchants of death outperformed the market. And in the systems thinking analysis we see the reinforcing loops abound. Congress gets oodles of campaign financing from these industries, which pour billions into professional lobbying, often by lobbyists who used to work in Congress or in the military (these are gold-plated revolving doors). More weapons mean more profits means more… and so it goes.

Addiction, as noted by system thinkers, is an outcome of depending more and more on what seems a quick fix over time and investing less and less on core solutions. This is the treadmill members of Congress are on, bringing home the military bacon to their district or state regardless of the harm those highly saturated fats are for the human family. If you want to get re-elected, conventional wisdom is to bring home the pork. And the greasy pork is often on the menu via the military budget in every congressional district. As President Eisenhower warned us, the military-industrial-congressional complex has cooked the system. To vote against the failed and troubled F-35 boondoggle, which has components of it manufactured in over 400 of the 435 districts, is to court a litany of catcalls underwritten by the industry.

Breaking away from this weapons addiction will require a long-term commitment to redirect our attention and energies towards the real tidal wave of security threats that will affect all of us which come not from autocrats in Russia or China but from the co-mingled crises of climate chaos, gross inequality, injustice, and ecological unraveling. That polycrisis is picking up steam much quicker than most had charted. They are driving millions from their homes, seeking respite from the trauma of insecurity. As President/General Eisenhower said,

“Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed. This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all in any true sense.”

Lasting

solutions require building trust, which simply can’t be constructed overnight.

Trust needs to be nurtured, worked at, and encouraged. Transparency is

essential, as is verification. Third parties are often helpful, perhaps even

necessary, to transition to a trusting relationship.It simply takes courage to build trust, to be vulnerable, especially with those we see as enemies.

There is certainly a role for oversight, whether through an international body such as the UN, or at a local unit of government or citizen commission. If we redirected even 10 percent of the weapons budget towards these efforts our long-term possibilities for peace and security at home and abroad would improve. If the waste and fraud rampant in the military procurement mess were eliminated it would make this transition easily affordable and us more truly secure.

Einstein observed that doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results is a definition of insanity. Guns don’t protect us. They are an addiction that must be cured if we are to achieve real human security. Let’s work to build a world of true human security for all in communion with the web of life that we share. We need the courage to tackle our addiction to weapons and build the trust that can allow us all to live secure and fruitful lives. Time is running out.